It's busy at the crossroads

How metaphor inspires or imprisons our imagination

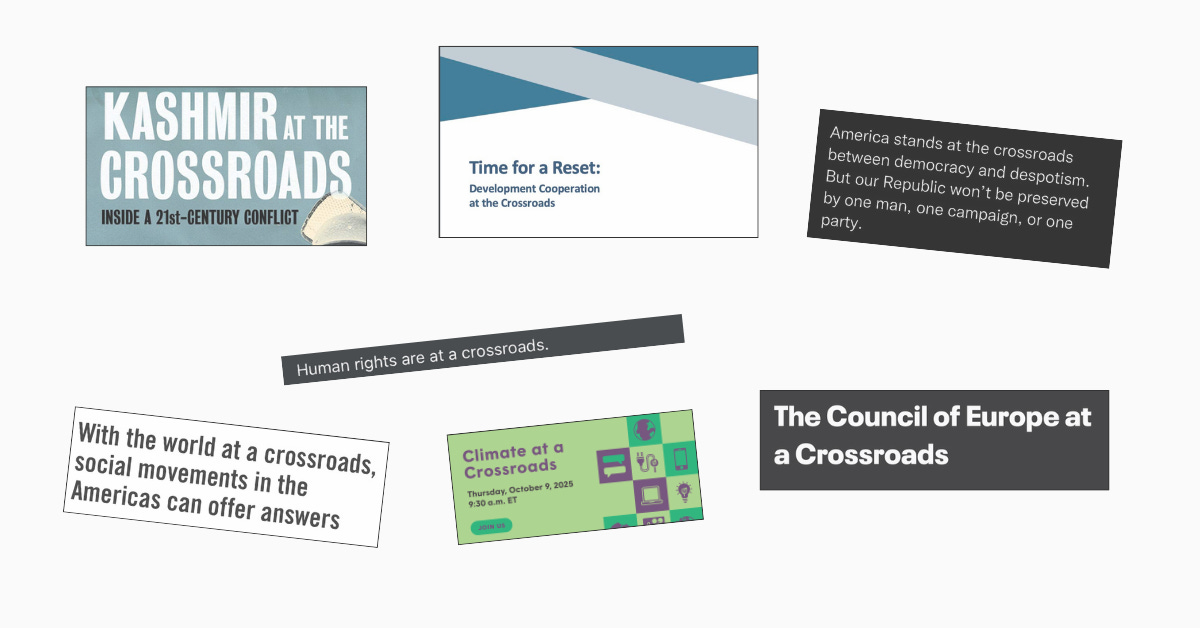

The crossroads are congested these days. Democracy is there, of course. So too are development, small states, the climate, the G20, and America. The world itself shows up sometimes, a bit harried. Institutions form a queue, clutching briefing papers and glancing nervously at each other.

Any crossroads worthy of its name offers three roads to pick. We rarely hear about them, of course. The metaphor usually just signals a time of uncertainty or a decision point. And sure, it can be useful (and sometimes literally true). But it’s tired. Probably so are many of us who use it.

The metaphors and constructions we choose can either reveal or obscure. They can open up our imagination or they can trap us in patterns of thinking about the world that misdirect our diagnoses and constrain our sense of what is truly possible.

“Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking, even if only to convey that thing you think everyone is saying” — Timothy Snyder

Metaphors are more than just linguistic baubles. They are woven into how we make sense of reality; they impose a pattern on the world.

As George Lakoff and Mark Johnson wrote in their classic text, Metaphors We Live By, metaphors structure how we perceive, how we think, and what we do. Metaphors help us in turn to create the realities that reinforce the metaphors.

So when we select a metaphor in the context of talking about issues like injustice and inequality, we are suggesting a certain diagnosis of the problem and the way out of it. But do we even know we are doing it?

In his much-cited 2017 book On Tyranny, the historian Timothy Snyder offered twenty lessons from the last century on how to resist authoritarianism. It is the ninth exhortation that has lingered in my mind: be kind to our language.

Snyder argues that it is when we begin unthinkingly reciting the same constructions over and over again that they become unquestionably, irrefutably true. Familiar sayings metabolise concepts and fix them in our minds so that for a time, no other way of imagining can be true.

(An aside: this is why politicians repeat phrases endlessly. This is how we come to associate words like “migration” with “illegal” instead of “people” and “solidarity”).

Snyder is making the point to show how societies fall into line behind tyranny. But the same insight applies whenever we reach reflexively for the same formulations in any context, whether they make sense or not. We submit to a template. Our imaginations exhausted, we stop thinking about what we mean and let the linguistic preset determine the meaning instead.

In my first post I wrote about how stuck we seem to have become. The crossroads is the metaphor par excellence for stuckness. This is the place where we stop and ask, where can we go?

Maybe we find a kind of tyranny lurking at the crossroads, watching with a wry smile as we take our place in the line. Welcome, it says. This is where we all find ourselves eventually.

But what if there are no more roads to find? What if we need to look instead for stepping stones across a rugged and boggy landscape?

The crossroads give way to another mental template: strategy. Here we move from the grammar of uncertainty to the grammar of war. How to find direction becomes how to win. In the realm of social change, this can be a valuable shift — but it has a shadow side too.

Any good bookshop is likely to carry Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. Head to the Business and Management shelves to find the seminal text on strategy. Essential reading for any competitive undertaking. But there is a caution here for those in the sector-without-a-name (human rights, climate, peace, inequalities, etc.) working for a more equitable, peaceful, just world:

“[I]f victory is long in coming, then men’s weapons will grow dull and their ardor will be damped. If you lay siege to a town, you will exhaust your strength.”

When you look at burnout among those who dedicate whole careers to a siege that may never end, you might start to wonder if we chose the wrong paradigm. What if the task is less a tussle for victory and more a quest to manifest ways of living that are more in tune with the kind of world and people we want to be? Is strategy still the right lexicon here?

“When a truth is spoken it becomes untrue … Which is why certain things should not be said” — Anita Mason

There is nothing wrong with the crossroads, nor with strategy, nor any others besides. All can earn their place. But we need not be imprisoned by their logic, repeating them endlessly until we no longer mean them — or know what they mean.

This matters more than we may realise. Language and truth hold each other, but at a distance. The fixity of our formulations can distort our imagination about what is true or could be true in future.

In other words, getting unstuck may rely on us opening ourselves to different ways of framing things. As Lakoff and Johnson say, new metaphors can give us a new understanding of our experience and of our sense of possibility.

There has already been a shift in social change work towards using metaphors of the garden. That helps us to think about change as organic, gradual, something to cultivate and guide and prune, something that may be beset by pests or that dies back only to regrow and finally mature. It changes the whole way that we think.

Then there is jazz, a metaphor that Mónica Roa has expounded in the context of activism. As a dedicated jazz lover, I find this one promising. It offers a way to describe holding a certain beat, resisting the urge to essentialise things. Rebecca Solnit quotes Cornel West’s idea of the jazz freedom fighter, in which the mere musical form becomes something much richer:

“a mode of being in the world, an improvisational mode of protean, fluid and flexible disposition toward reality suspicious of ‘either/or’ viewpoints.”

Jazz is fluid, it is communitarian, it is all about improvisation and responsiveness and building collectively towards moments of soaring beauty. As the first notes are played, there are many more than three roads to take.

If we are going to get unstuck, we need to liberate our imaginations from tired formulations that simply reinforce the stuckness. We need to be open to new vocabulary, new grammar, new genre alike. From there, who knows what new stories and possibilities may emerge.

Metaphors are at the crossroads. So perhaps we need to install a roundabout. Or a jazz band.